I’m sitting at a makeshift desk in a garage overlooking a crop of man-tall maize. At the far end of the field, there’s a line of bright trees, framed by a rising bank of heavy cloud; cumulus or cumulonimbus, the kind that give the impression of architecture-in-bloom, cities in the ether. There’s a dry breeze shaking the limp maize leaves. But it won’t rain. This morning I helped my stepdad measure the camber of the adjacent road. He’s worried about run-off, flash-flooding, when the rain does come. We had to dodge traffic: it’s a long, straight Roman road where military vehicles, livestock transport, 4x4s and boy racers speed past. A little bit further down, in a parched meadow, an ancient black horse veiled in a fly mask kicks-up dust. Across the fields from there is the river: a thick, crooked stretch of slow water – a local swim spot – where it’s not uncommon to see kingfishers, cutting through the leaf-shade like phosphorescent aura. Everything here seems perpetually cast in a coppery-green light.

I’m trying to work, but I can’t. Mostly I just want to watch The X Files and sleep, and dream. Temporarily, or permanently (or subconsciously intentionally?) I’m squeezed out of London, where the rental market has become totally impregnable. My shrinking budget, combined with the rapid metabolism of SpareRoom – something like the worst dating app in existence, with its orgy of upbeat, alienating £850pcm+ house-share ads, its glut of millennial live-in-landlord midcentury-fetishists – had truly begun to give me palpitations. I liked this quote from Tennessee Williams I recently stumbled upon, in which he describes those of the ‘artistic world’ as ‘little gray foxes’ whose natural enemy is the landlord. ‘We expect no quarter from them and are determined to give them none. It is a fight to the death, never mistake about that’.

Things are quieter here: I’m at my mum and stepdad’s house, in Wiltshire, a temporary situation somewhere between ‘rock bottom’ and ‘necessary transitional period’. They moved here – or moved back here – last spring, having spent several years elsewhere in the South West. This house is a couple of hundred meters from the Somerset border. It’s ten miles from where I was born, and, in the other direction, ten miles from where I grew up. It’s a house in-between things: both home and not-home. I’m immersed in a familiar landscape – the landscape of my childhood and adolescence – without being inescapably submerged in all the exact places, streets, fields, lanes, tree-shadows, supermarket carparks, Texaco forecourts, of that time: places which are psychically heavy. Places which, to merely pass through them, might result in an episode of the ‘blue devils’ (Williams’ pleasantly devitalizing pet-name for depression). Affect does inscribe itself on the physical environment: I think this is how places come to be haunted.

Every time I come back here, I learn something new about my personal history. At the pub last night, I asked my mum how much rent she paid on her first house with my late dad. She couldn’t remember. But she did remember that when they moved in, they found, in a closet under the stairs, three bin bags full of Alsatian dog hair left by the owner. And a safe. A huge, heavy, leaden safe. In the false bottom, there was half a gold sovereign, which they cashed, then used some of the money to buy me and my sister Christmas presents that year. My parents would have been the age I am now, maybe a year or two older. It’s an unreal story. From another era. Did it really happen?

Carson McCullers wrote that many authors ‘find it hard to write about new environments that they did not know in childhood. The voices reheard from childhood have a truer pitch. And the foliage – the trees of childhood – are remembered more exactly.’ It’s a sentiment that feels instinctively right. It chimes with many other, more well-known, quotes about the overlap between home, childhood, and the urge toward creative expression (the Robert Frost quote, often touted in Creative Writing classes, immediately comes to mind: ‘a poem begins with a lump in the throat; a homesickness’). I find McCullers’ quote interesting because of its seeming conflict with her more prominent statements about writing and creativity; her declaration, for instance, that ‘reality alone has never been that important to me’. She asks, ‘what is more intimate than one’s own imagination? The imagination combines memory with insight, combines reality with dream’.

But reality and dream, imagination and exactitude weren’t, for McCullers, mutually exclusive. They were concomitant forces. Combined, they generate the particular climate of her fiction – which is almost exclusively set in the Deep South of her childhood – one that gives rise to her central themes of nostalgia, love, and loneliness (or the reach of loneliness: the desire for communion). For McCullers, the trees of childhood are remembered exactly, and they are also an illusion: a paradox that doesn’t lessen the truth of her art, but strengthens it.

When I’m back in this area, drinking with old friends – friends I’ve known for most of my life – the pull toward reminiscence can be strong. Do you remember when…? Do you remember this the way I remember it…? The reality of our shared personal history, here, in this coppery-green landscape, becomes both sustained and suspended by a kind of collaborative myth-making, a joint exercise in imagination: we repeat the same stories again and again, polishing and refining them each time, letting go of contradictions in the telling, impossibilities or improbabilities in the narrative, so that they become as smooth and hard and reassuring as a good skipping stone… Or like guide-knots in a huge length of rope… One end tied to our waists, the other, looped around a tree trunk many years in the past.

❦

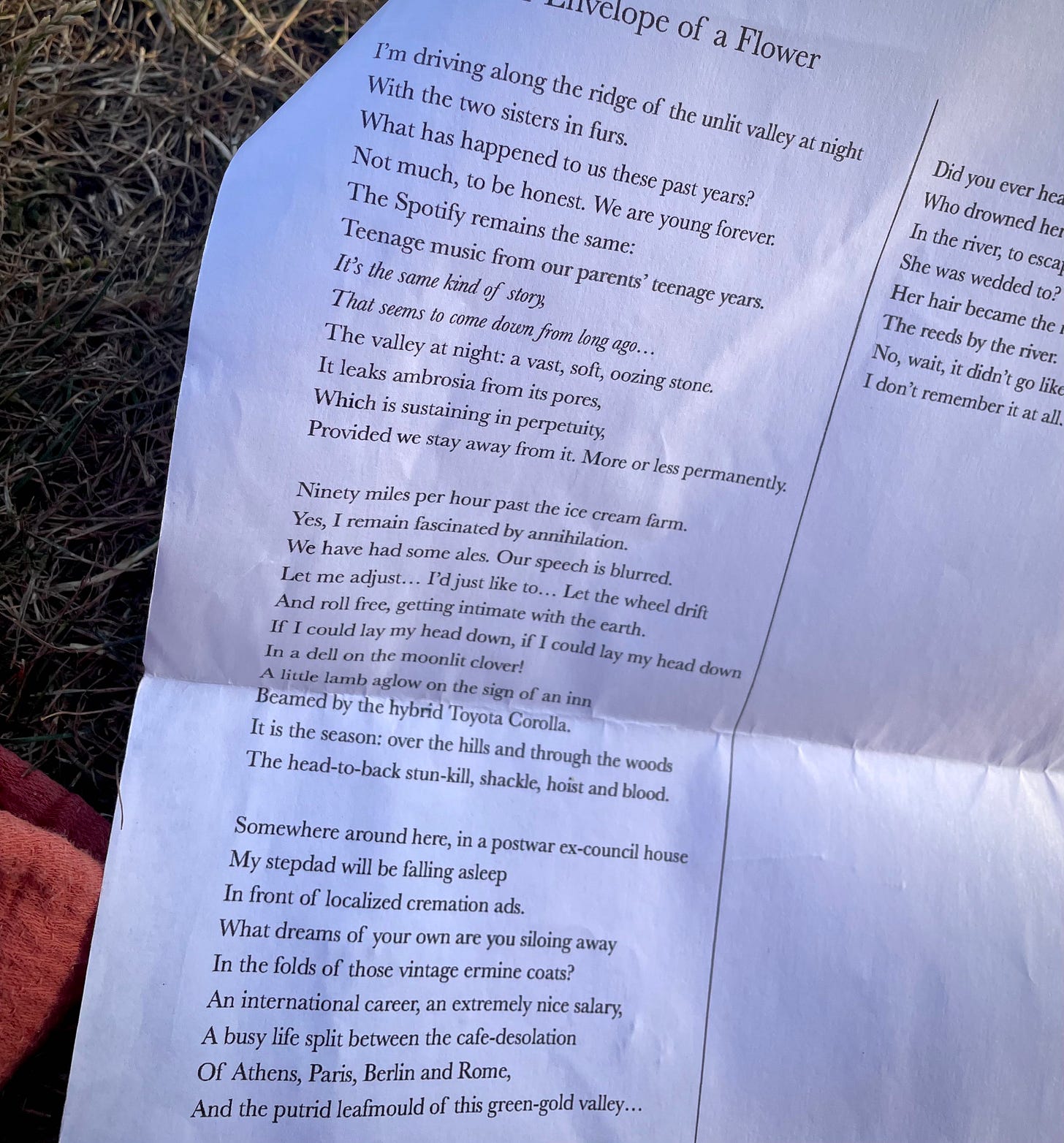

Appended here, a clipped photo of a draft of a poem, the first three stanzas of which feel finished, and which echo with these ideas. Written back in spring. So long – !